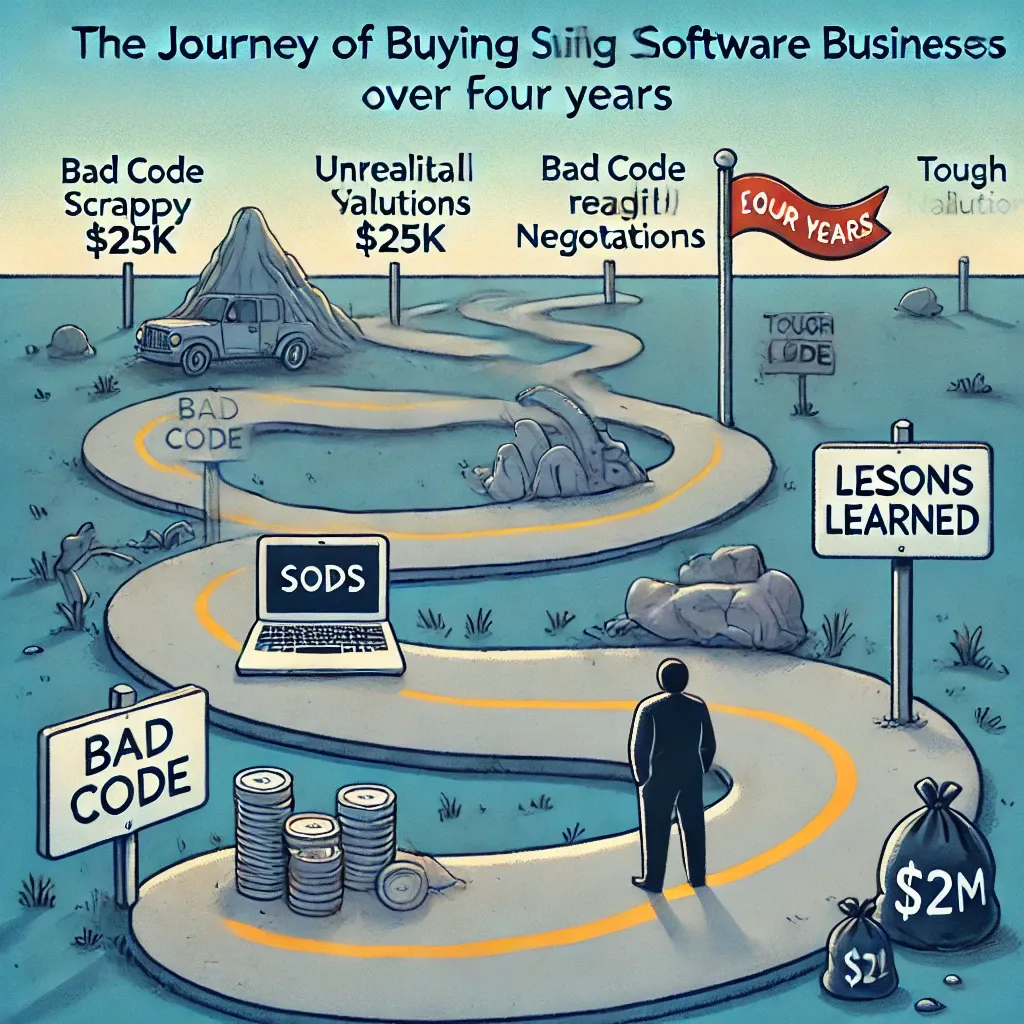

Everything I've learned about buying small software businesses over the past 4 years

XO has been a tough ride. We had some wins, some losses and overall haven't made much money. We still own and operate assets and may buy more in the future so the full financial picture isn't clear yet.

It took us about 4 years to finally be able to buy $1-2M businesses, so in some ways the lessons below are exclusive to the winding road we took to get to where we are today. I'm still bullish on our larger acquisitions like onsched and journey. It's been awesome to have Danny and Henry as co-founders along the way and I think we've made life long friendships in the process. There are only a handful of people on earth I trust to share a bank account with and Danny and Henry are on the top of that list. And despite not making it rain quite yet, I do think what we've been able to accomplish so far is pretty cool. I certainly didn't see a path towards us regularly buying low 7-fig businesses at the start.

The software market at large other than the mag 7 feels like a wholly different animal than it did a year ago, 2 years ago, 4 years ago. I'm not sure if it's AI, the lower demand for software engineers, offshoring, etc, but business has been harder the past year or two than at any other time than i can remember. The exception there would be the great recession in 08 when I was still in school. In 2020/2021 you could buy a business for a reasonable price, get some reasonable growth on social media, and then expect to be able to sell it. That feels less true today. Channels are crowded. Software is easier than ever to build. There are new "hold co's" popping up every day. Those with distribution first will win.

If you're reading this hoping whether this article will tell you whether you should or shouldn't buy a business, you're in luck. Don't do it. If you're going to do it anyways, please read on. This is a generally unfiltered list of all the one off things I've jotted down over the past 4 years.

- Mostly crap businesses are for sale.

- There is a reason a seller is selling and it's because they don't think it's going to make them money anymore for one reason or another. Fatigue in a biz is from failing, not from winning. If they're tired of winning and want to win elsewhere, you probably can't afford it.

- If you are in the mix to buy it (i.e. its listed on acquire or something), then they've already explored (and possibly failed) at a strategic acquisitions, raising more money or both. This doesn't mean it's a bad business but it does mean it's not an obviously good one.

- You're actually in the business of sourcing deals. If you don't enjoy reading through hundreds of CIMs, or listings and then talking to people to figure out if what they're saying is to be trusted, then this is not the business for you.

- All of the marketplaces suck at giving you a good enough search tool to actually filter to find suitable businesses. Having relationships with brokers and having a team of people to help you sources is extremely helpful.

- The code you are buying is, generally speaking, atrocious. not just bad, but old and bad. This seems to get worse the larger the business is.

- People are generally good but there are bad actors. We've experienced some deeply unethical behavior. If you're "spidey sense" is tingling during diligence... trust your instincts and back out, it's not worth it.

- Cash flowing saas businesses is extremely hard.

- Software's "80% gross margins" is BS and in practice is more like 65-70%. AI companies who have costs that scale linearly with revenue have it worse. When public companies report they have like 80% gross blended margins across an entire company, that's called having a good accounting team. If you were to do the napkin math there's no way in hell they do 80% gross margins.

- Most of the time, the seller has no idea about M&A and it's very difficult for you as a person with a vested interest in the transaction to educate them on it. Typically they have to go learn elsewhere.

- People still have extremely unrealistic expectations about how much software is worth. People aren't really paying 3x anymore down market where we play. it's 1x-3x max. Any more than that is really a strategic player who sees much more value long term.

- Operating a business without dedicated full time employees is a grind and doing multiple in parallel is a great way to burn out. Buy businesses with teams.

- Diligence is really just about finding where all the bodies are buried. very hard to say what to do about it until you find them all.

- Businesses that were growing when we bought them tended to stay growing. Businesses that weren't growing when we bought them tended not to grow at all despite our best efforts. See above, the founders couldn't figure it out either.

- You're probably not buying a business with product market fit. This was why for a while there we just bought single purpose apps. This was as close as we could get to PMF at a low price point.

- Dev tools worked out best for us. The businesses we 10x-ed, 5x-ed, etc. those were all dev tools.

- If we hadn't had a year or two of free cloud credits, I genuinely think XO would have shut down in year 2. They were insanely helpful for us to make mistakes and figure out an operating model.

- If your core skill set is growth, then try to start something from scratch. the alpha there is larger and the time horizon to a bigger payout is shorter than buying. Our best deals took 3 years to mature. They looked good along the way but the real payday didn't happen for 3 years.

A year in the life

The work is roughly this. You (yes you, bc you probably dont have a team yet), comb through hundreds of listing, hop on dozens of calls, make offers on a handful and could close on 1-2. You can collapse this time period into 30 days or it can string out over a year, but it's the same quantity of work. By the time you get access to everything in diligence, you are pretty pregnant with the idea of buying it, so is the seller, and you're going to find all the warts (and assume there are more you do not have the time or visibility to find. These will show up at an inconvenient time in the future). Let's say you accept the challenge and close the deal. Yay. All that work you did? Throw it out the window, because you're now really operating the thing and it's going to (best case) look like a cousin to what you thought you were buying. Worst case is it's going to look and feel like something completely different (and it's your fault for not catching this sooner). At this point, all those obvious growth levers you identified in diligence don't look so obvious. You find evidence that they have been attempted before and didn't work. You may have ideas to try new things, you might have 30 ideas, but the team is busy, you're busy, so you have to implement them, or dip into your growth capital to get it done. In a month you'll know if you should shift. After about 3 months, you'll know if the math you did in your financial plan makes any f*$ing sense at all.

So overall when you acquire something and it works, it's the greatest thing in the world. You bought something already on a path and you shepherded it farther down that path and were rewarded for it. When it doesn't work, you really wonder whether you should have just put your $ into the S&P and done something else with your time.

Online, people tout acquisitions as a fast path to wealth creation. The more sobering reality is that acquisitions are also difficult. Are they as difficult as starting from scratch? That depends on you and your skill set.